Pink Sand Press: What Can Happen When Your Agent Decides to Become Your Publisher

Posted by Victoria Strauss for Writer Beware®

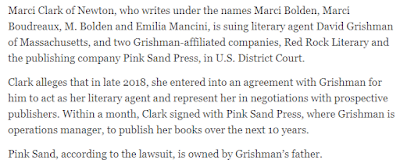

Last week, several people drew my attention to this article in the Des Moines Register. “Iowa Romance Writer Sues Over Efforts to Have Ghostwriter Take Over Series.”

If your “conflict of interest” radar is screaming right now, it should be.

Clark’s complaint (which you can see here) accuses Grishman et al. of breach of contract, breach of fiduciary duty, and fraudulent concealment, and alleges a variety of malfeasance, including concealing the family connection, and invoking an allegedly non-existent contract clause to justify buying out the final two books in an uncompleted series and hiring a ghostwriter to write them. Clark is seeking to terminate both her RedRock Literary and Pink Sand Press contracts, and to receive an award of “lost profits, damages, costs, and attorney’s fees based on Pink Sand’s breach”.

As of this writing, Grishman hasn’t filed a response to the lawsuit, but he did have this to say to a local reporter:

I will have more to say about the complaint. But first…

SOME BACKGROUND

Marci Clark wears many hats. In addition to being the author of multiple novels under several pen names, including Marci Bolden, she has worked as a freelance writer and as an editor for several small publishers, including Lyrical Press. She’s also the owner of Nerdy Kat Book Services, which provides design, consulting, editing, and other services for authors. According to her bio, she has an MS in publishing (keep that in mind as you read on).

David Grishman is a commercial loan officer at Bank of New England and serves on the Select Board of Swampscott, MA, where he resides. He also served for several years as CEO of Waterhouse Press, a publisher founded by successful self-published author Meredith Wild (according to this 2016 New York Times article on the publisher’s founding, Grishman is Wild’s brother-in-law). Grishman brokered some pretty big book deals at Waterhouse, but by September 2018, he had vanished from the company website.

Grishman seems to have set up RedRock Literary* in fairly short order following his departure from Waterhouse. Its domain was registered on the last day of October 2018, quickly followed by two Massachusetts business registrations: RedRock Literary Inc., filed in November 2018, and a conversion to RedRock Literary LLC, filed in December 2018. (As pointed out by IP attorney Marc Whipple in a lengthy analysis of Clark’s complaint, the conversion to RedRock Literary LLC happened just days after Clark signed an agency contract with RedRock Literary Inc.–which contract doesn’t seem to have been amended to acknowledge the change. This, according to Whipple, is “extremely unusual”.)

Beyond the registrations, the lawsuit, and a couple of photos accompanying a trademark application, there’s no evidence of RedRock’s existence: no website, no social media, no reports of sales.

Pink Sand Press is somewhat more corporeal, with a website and a Facebook page. That’s not to say it’s a healthy company. For one thing, it is no longer a functioning corporation: it was involuntarily dissolved on June 30 of this year by order of the MA Secretary of State (Clark’s lawsuit has been amended to acknowledge this). Again according to Whipple, that usually happens when a corporation fails to file reports on time.

Apart from the books it has published for Clark, Pink Sand has virtually no track record as a publisher. A search on Amazon turns up two other authors and five other titles–but the status of those titles is unclear. They are nowhere to be seen on the Pink Sand website, they don’t appear ever to have been promoted–or even mentioned–on Pink Sand’s Facebook page, and four of them–by Jeanne De Vita, writing both as herself and under the pen name Callie Chase— have either been taken out of print or are listed as out of stock or unavailable everywhere but on Amazon. (Interesting side note: De Vita was an editor at Waterhouse Press.)

THE CONTRACTS

Both of the contracts Clark signed–the RedRock agency contract and the Pink Sand publishing contract –are attached to her original complaint.

The agency contract looks reasonably standard to me, though it imposes a three-year term that the author can terminate only in the event of breach by the agent–not ideal. It also has an arbitration clause, which could complicate things for Clark’s legal effort to be released.

The publishing contract, which covers a whopping 28 titles, is another story. It includes some really terrible clauses, particularly in regard to payment.

For instance, here are the royalty rates for hardcover publication:

This is seriously nonstandard. Mass market paperback royalties are also substandard, at 5% of wholesale.

Of course, both of these provisions are moot, since Clause 4(a) of the contract stipulates publication only of “an e-book and trade paperback edition”–but there are big problems with royalties for those formats as well. Ebooks are paid at just 15% of net (even the big publishers typically pay 25% of net, and most small presses pay considerably more). As for trade paper royalties, there is no mention of them in the contract. At all. (!!!)

Subsidiary rights payments too are hugely, one might almost say rapaciously, substandard, with the publisher keeping 85% and the author getting just 15%. These include foreign language, book club, and numerous other rights that are typically allocated at least 50/50 between author and publisher.

Other lowlights: an overly lengthy grant term (10 years); no advances for certain of the many backlist titles acquired; a non-competition clause that bars Clark not just from publishing competing works, but from publishing anything until the terms of the contract have been completed; an agency clause that empowers RedRock to increase its commission for subagented rights sales beyond the commission rates stipulated in the agency contract; and a clause that empowers Pink Sand to retain rights for five years to a delivered revision it declines to publish, unless the author can find another publisher willing to hand all the author’s earnings over to Pink Sand until advances have been repaid. (Good luck with that.)

It’s hard for me to imagine any reputable publisher offering a contract like this, or any reputable literary agent advising a client to sign it. I see some pretty atrocious contracts from inexperienced publishers who don’t know any better, but Grishman is not inexperienced. Waterhouse Press is a successful house, and he worked there for years.

Make of that what you will. Make what you will, also, of the timelines involved. David Grishman incorporated RedRock Literary (for the first time) on November 13. Less than three weeks later, on December 2, he signed Clark as an agency client. Six weeks after that, on January 15, Steven Grishman incorporated Pink Sand Press. Clark’s publishing agreement was signed just eight days later, on January 23.

The whole thing has the feeling of a rush to pin something down.

THE COMPLAINT

Here are Clark’s principal allegations, with my comments. (I’m not a lawyer, but I have Thoughts.)

Allegation 1. It was not revealed to Clark that Pink Sand was owned by Grishman’s father until after she signed the contract. Instead, she alleges that she was told that the company was “a startup company that would be owned by Grishman and Matthew Bernard, Grishman’s friend.”

It’s possible to imagine a situation in which the alleged statement by Grishman was not misrepresentation–at least, at the time it was made. Suppose, for instance, that the described joint ownership really was the plan in December, when Clark signed the agency contract–but later those plans fell through and Grishman turned to Dad instead.

Even in this hypothetical, though, everything would have changed on January 15, when Pink Sand’s business registration was filed in Steven’s name. In terms of conflict of interest, there’s not a lot of difference between your agent owning your publisher, and his father owning your publisher while your agent just works there–but at a minimum, Clark should have been informed. It sure seems like there was ample time for that to happen before January 23, when Clark signed the Pink Sand contract.

Allegation 2. Pink Sand did not file copyright “applications” (presumably what’s meant here is registrations) for any of Clark’s works, as the publishing agreement required it to do.

I checked the public copyright catalog, and of the nineteen Marci Bolden books published by Pink Sand, sixteen are indeed registered.

I can’t see any pattern that would explain the three that aren’t registered, although they are the only standalone titles. They’re also the only titles available solely as ebooks (the rest are available in a variety of formats). Weird.

Allegation 3. In March 2020, after a fourth novel in one of Clark’s series was delayed by extensive developmental editing, Clark alleges that Grishman informed her that the publisher would be buying out the final two volumes in an uncompleted series and hiring a ghostwriter to create them, claiming that “she had no choice because of a clause in the Publishing Agreement that allowed Pink Sand to use a ghostwriter to finish the series that would be published under Clark’s name.”

Clark alleges that there is no such clause. I agree. I’ve read the contract several times, and I can find no wording that’s even remotely similar to what Clark alleges Grishman told her. If this allegation is true, it would constitute some serious gaslighting.

Allegation 4. In February 2021, Clark and Pink Sand executed an amendment to the original contract that “expressly changed the Publishing Agreement to only require Clark to submit manuscripts for copy editing, not developmental editing.” Clark alleges that Pink Sand breached this when it “insisted on conducting developmental edits before accepting Clark’s manuscripts for publication.”

Here’s the amendment:

This doesn’t seem to me to be as unambiguous as the complaint alleges. Yes, “developmental” is crossed out and “copy” is substituted–but only in connection with establishing a delivery date. There is no wording that explicitly excludes developmental (or any other kind) of editing. Maybe the intent was to exclude it, but to me (and again, I’m not a lawyer), the actual wording leaves something of a loophole that could enable Pink Sand to argue that it wasn’t in breach: for instance, it could claim that when the works were received for copy editing, it was realized that they needed developmental editing, so Pink Sand went ahead and did that since it wasn’t specifically prohibited from doing so.

Allegation 5. In May 2021, Clark and Grishman agreed on a September 24 submission date for an unnamed manuscript. But in August, Clark alleges that she was told her submission was late; and on September 15–at which point, remember, the ms. wasn’t actually due yet–Pink Sand informed her that she was in default and her royalties would be withheld “until the parties came to an agreement to end negotiations and terminate the Publishing Agreement.” (Clark did not turn in the manuscript.)

The complaint doesn’t include any documentation of this claim. But once again, the timelines are interesting. Pink Sand was dissolved as a corporation on June 30. According to Clark’s complaint and the Pink Sand contract, September 15–the day she alleges that she was prematurely told she was in default–was also the day royalties were due.

Hmmmm.

FINAL THOUGHTS

There is much here that it is impossible to know right now. The only documentation provided to address the many allegations in Clark’s complaint is the two contracts, and as of this writing, the Grishmans have not yet filed a response to tell their side of the story.

There are situations in which agents or agencies that double as publishers can avoid major conflicts of interest–primarily by maintaining a wall between the agenting and publishing sides of their business (agency clients are never offered publishing, other than possibly for represented backlist works that are out of print; and publishing clients are never eligible for agenting). There’s a whole section on the Literary Agents page of the Writer Beware website that addresses this issue.

Clark’s situation, though, seems like a textbook case of unavoided conflict of interest. Even had the Pink Sand contract been perfectly fair, Grishman, as Clark’s agent, could not adequately represent Clark’s interests when presenting it to her, because as a Pink Sand employee, he was also representing the publisher’s interest in having her sign it. This is why the AAR prohibits members from representing both buyer and seller in a single transaction.

Of course, the Pink Sand contract is not fair. One of the things I find most peculiar about the whole mess is that Clark was not a publishing neophyte when she signed it. She’d published several books, worked as an editor for other small presses, and had an MS in publishing from the University of Houston. Wouldn’t those terrible royalty clauses–at the very least–have rung some warning bells?

I’m not casting blame. But this is one of the things that makes me think that there’s a lot more to the story than is currently apparent.

Stay tuned.

* David Grishman’s RedRock Literary Inc should not be confused with Renata Kazprzak’s UK-based Red Rock Literary Agency.

UPDATE 1/24/22: Well, this is a surprise. Marci Clark has dismissed her lawsuit (without prejudice, which means she could re-file). The Grishmans filed several documents, including notices of appearance and a corporate disclosure, but never answered Clark’s complaint.